We identify the hotspots and where to avoid super contagious areas

After several years of studying pandemic data, it has been shown that the main route of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs through aerosols, that is, breathing the coronavirus when it is exhaled by an infected person, whether or not they have symptoms. This is one reason why the recommendation to do outdoor activities has become so popular: as the concentration of aerosolized virus is very small, the risk of getting infected is as well.

“Many contact tracing studies show that it is 20 times easier to get infected indoors than outdoors,” atmospheric chemist José Luis Jiménez, professor at the University of Colorado, explains to El Confidencial. “It is also known from the databases of infections in super propagation, that there are many more infections indoors than outdoors, and the former has many more cases.”

Aranet4 – CO2 meter used in this report

The amount of CO2 (air exhaled by other people) in a certain room is an indicator of the risk of contagion

Jiménez, one of the most renowned academics in the study of the correlation between the concentration of aerosols and COVID-19 infections, points out that the key is to ventilate the air in closed places with poor ventilation.

“The amount of air exhaled by other people in a certain room is an indicator of risk,” he says.

Fortunately, we have devices capable of quantifying this risk: CO2 meters.

The basal amount of CO2, as we know from climate change studies, has increased in recent years to exceed 400 parts per million air molecules. It is what we find when walking through the field. However, indoors, the danger increases:

“If there are 800 parts per million in a room, this means that 1% of the air we breathe we are breathing a second time.”

Equipped with one of the most accurate gauges on the market, we set out to check where the risk really lies in our day-to-day lives. The indicator will turn yellow when the limit of 1000 parts per million is exceeded and red when it exceeds 1400 ppm. The goal, therefore, is to be able to live below 800 ppm in a city like Madrid. Let’s see if it is possible.

House

People: Two Measurements: Without protection

Upon arrival at the apartment, the meter shoots from 623 to 1682 ppm in a matter of 15 minutes. The windows are closed and the heat is on. After turning off the heating and opening two opposite windows for ventilation, the carbon dioxide concentration drops back below 800 ppm. An hour later it is at 585 ppm.

Not surprisingly, many outbreaks occur in home settings. At a family meal, it is not normal to adopt protective measures, but improving ventilation can help a single infected person not end up infecting everyone else.

Travelling by car

People: One – Two Measurements: Without protection

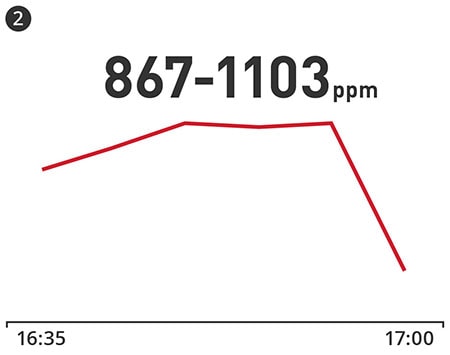

The second place where the meter registered the highest concentration peaks was when travelling by car. When you’re travelling alone it can easily be under 700 ppm, but if someone else gets in the car and the windows are closed, the needle starts to climb rapidly above 1100 parts of CO2 per million in just ten minutes.

One of the steepest descents occurs precisely when getting out of a shared car. The meter went in a couple of minutes from 1098 to 484 ppm.

They are very sensitive environments. An elevator is too, but we hardly spend a few seconds sharing space in them. However, in a car one can spend much more time commuting and sharing exhaled air. It is therefore important to exercise extreme caution when travelling in a taxi or someone else’s car, even with masks.

At the university

People: 22 Measurements: Ventilation, capacity control, and seat separation

Many of the classes from the Faculty of Philology of the Complutense University have moved to the Paraninfo, a classroom with high ceilings, semi-circular bleachers and open windows. This allows that despite the fact that there are more than twenty people in the classroom, CO2 levels remain comfortably between 463 and 484 ppm.

Another test, in one of the corridors of the faculty, shows more or less similar values. It can go up or down in 50 parts depending on the number of people circulating at any given time, but the air concentration is usually kept at bay below 500 ppm.

Not surprisingly, the majority of infections in colleges and high schools are associated with extracurricular gatherings and group social gatherings. Even with better ventilation the risk always exists, but the possibility of a super contagion in the faculties is greatly minimized.

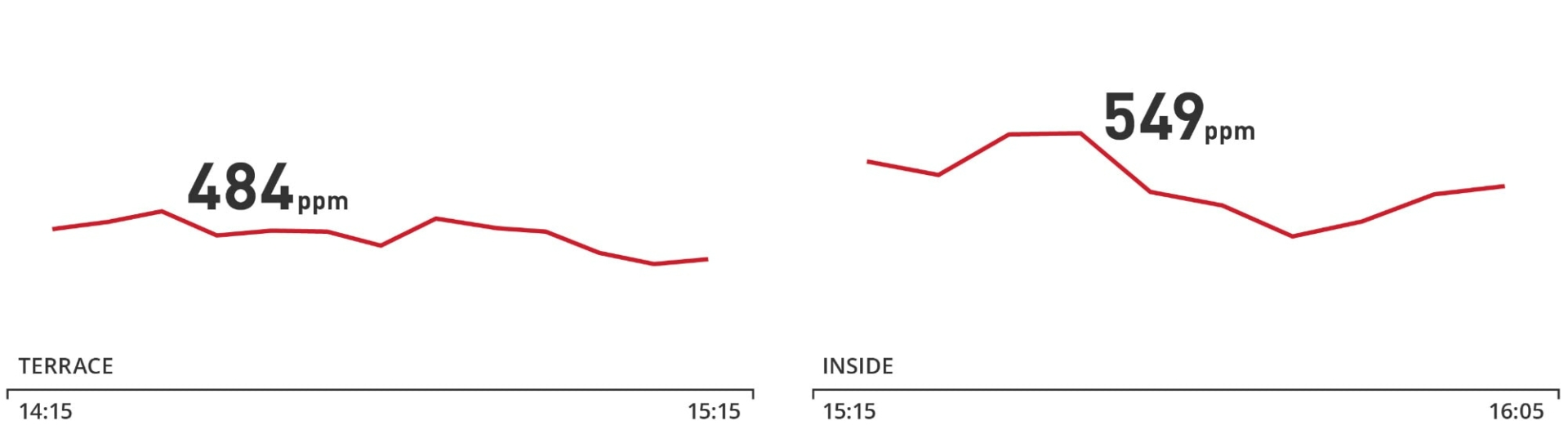

In the subway

People: Train Car half full Measurements: Ventilation, gauging control, no separation

Public transport is usually the object of suspicion, despite the fact that Jiménez and other scholars of the matter usually classify subway trips as low-medium risk. Why? Mainly, because people go in silence, the journeys are generally short and because the air flow is continuous between the people who enter and those who leave.

“In public transport, it depends a lot on which particular metro and which particular bus,” says Jiménez. “Modern subways tend to have a lot of ventilation and a very strong air change, which is positive. If the people inside keep a distance, wear masks, and do not speak, public transport can be quite safe”.

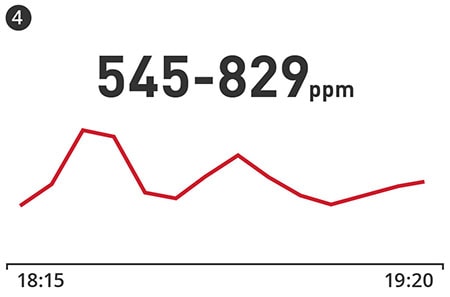

A trip on Line 6 from Ciudad Universitaria to República Argentina serves to shore up these impressions. Inside the wagon, where all the seats are occupied (there are no separation measures) and some people standing, the concentration of carbon dioxide ranges between 603 and 829 ppm, depending on the occupation of the wagon.

On the platform, almost empty after the train leaves, it is where the air enjoys a lower level, 545 ppm.

On the bus

People: Bus less than 50% occupancy (20 people) Measurements: No open windows or separation of spaces

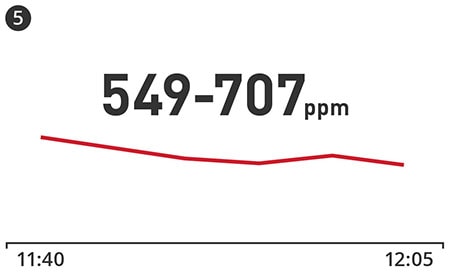

The bus is the other public transport where many people believe they are exposing themselves to contagion. A trip on line 126 between Barrio del Pilar and Nuevos Ministerios helps to allay some fears.

The CO2 concentration is even lower than in the subway. Depending on how full the bus is, it moves between 707 ppm and 549 ppm at the end of the line, when it was practically empty.

“It is highly variable, there are older buses that could have higher concentrations of CO2, so if the companies do not disclose these amounts, the users themselves could,”

says Jiménez.

In the mall

People: More than 50 people Measurements: No separation measures

Is shopping dangerous? As always, the time we spend inside a building increases the risk, but a priori, the wide spaces that usually exist in these rooms play against any super contagion event.

We do a test at El Corte Inglés de Nuevos Ministerios. Despite being located far from the door and from any air outlet – all the measurements we are doing meet these conditions – the CO2 concentration remains healthy below 600 ppm.

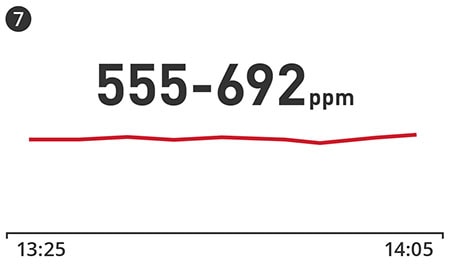

In the editorial office of El Confidencial

People: 20 – 30 Measurements: Separation of spaces, ventilation filters

Many Spaniards spend more than a third of their days in an office building, which is a problem given that many of them do not allow the modification of their ventilation conditions: for example, they do not have windows and only depend on the centralized air conditioning of the building.

In the Pozuelo de Alarcón office building where this newspaper is located, among other anti-covid measures such as the mandatory use of masks, the reduction of capacity and separation of jobs is being practised. Depending on the people who are there at any time, the CO2 levels within the newsroom range between 555 and 676 ppm, which is a fairly promising indicator, since measurements are made around noon, at the moment the busiest phase of the day within the newsroom.

Visit the doctor

People: 6 – 8 Measurements: Separation of spaces

Some studies carried out in the United Kingdom associate between 6% and 15% of infections to a nosocomial transmission, that is, produced in a hospital where one goes to treat any other disease or condition.

We made a routine visit to a hospital located on Calle Arturo Soria in Madrid. Some of the waiting rooms, especially when located in mezzanine or basement areas, lack windows and tend to gather a number of people for times that can be long, especially if there are delays.

Here the concentration exceeded 844 parts per million and at times touched 1200 ppm. This shows once again that, in the absence of adequate ventilation, the importance of other measures such as the limitation of capacity or the separation of seats increases, which allowed the influx in this room to remain below eight people continuously.

Comparisons

Is there much difference between eating on an enclosed terrace or inside a well-ventilated bar? And inside the house? To check this, we have used the meter in two different situations. These are the results.

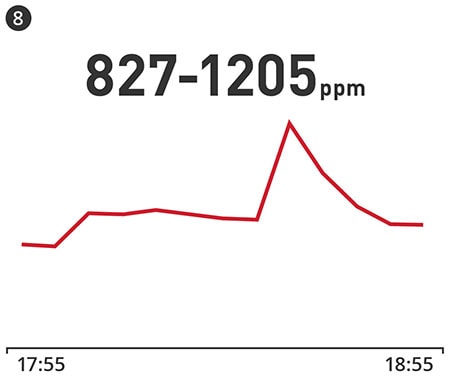

Closed house vs. ventilated house

The first night, without ventilating, the house reached 1566 ppm of CO2. The second, just opening the windows a crack, CO2 remained at around 750 ppm

47 square meters, two people and a dog – which also emits CO2 – on two consecutive nights. In the first one, all the windows in the house remained closed. Although the house at 9:30 p.m. was still ventilated, due to the effect of having opened the windows during the afternoon, in a matter of an hour we already exceeded 1000 ppm. Throughout the night and into the next morning, CO2 remained above 1200 and exceeded 1400 that delimit the ‘red zone’ on several occasions.

“Many people who are beginning to measure tell us the same thing, that where they find the greatest concentration is in their houses, which in Spain seem to be very well sealed and hardly any air comes out through the cracks or under the door”

explains José Luis Jiménez.

The following night, after an afternoon with hardly any ventilation at home, we reached 1566 ppm of CO2 around nine at night. At that moment, we simply opened the casement windows in the living room and another in the kitchen, to establish a very slight current.

As a result, overnight CO2, after hitting bottom 599 shortly after midnight, was consistently around 750 ppm. Almost 40% less than the night before with just a couple of windows opened a slit. The meter also makes it possible to verify that the night of the 11th (with closed windows) the temperature at home was between 18.5 and 19.8ºC, while on the night of the 12th (with slightly open windows) the temperature ranged between 18.3 and 19.9ºC, that is, an imperceptible difference in the cold in exchange for better air quality.

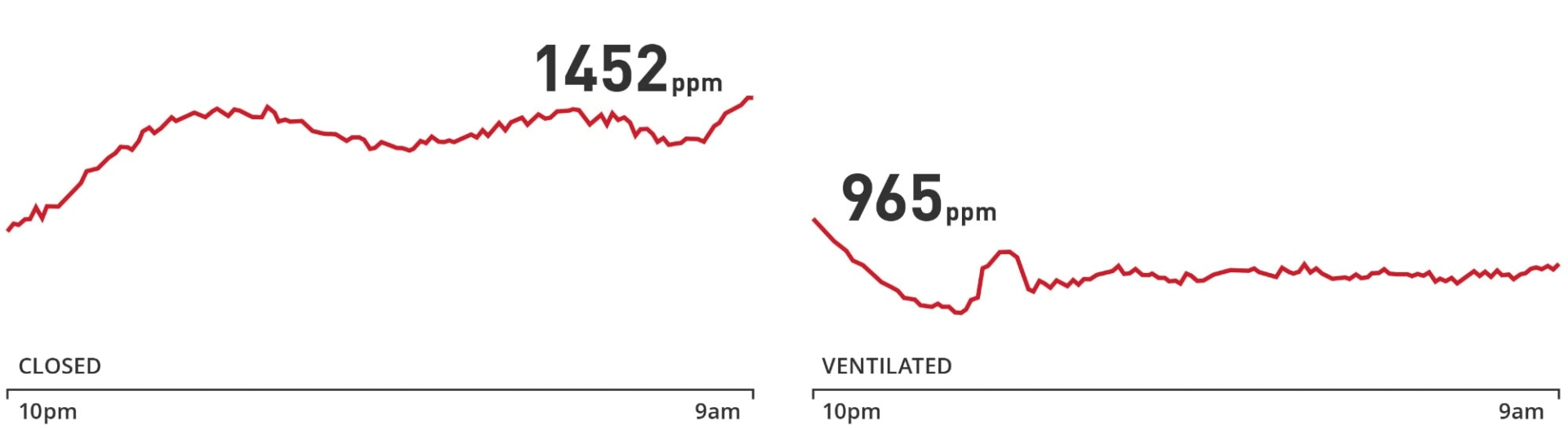

Eating on the terrace vs. eating indoors

Since the confinement ended, we always choose to eat on the terrace to have the minimum probability of contagion, but what is really the difference?

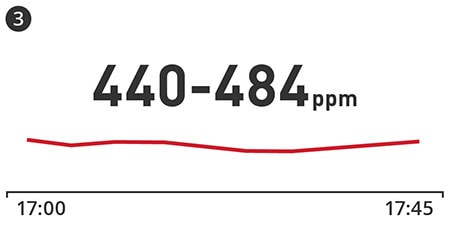

In a menu bar on Avenida de Europa, we opted to eat on one of those false terraces, with a roof and a couple of walls but one of them open to the outside. The good news is that the concentration inside these rooms – the occupancy was minimal at that time – is almost similar to what we could find in totally open-air terraces. Between 440 and 467 ppm.

For coffee, however, we opted for the interior of the bar, which fortunately has two doors facing each other and are permanently open. Despite having between 15 and 25 customers at all times, the CO2 levels were not tremendously higher than those registered on the false terrace, between 525 and 549 ppm of carbon dioxide.

It is an interesting experiment to lose the fear of entering certain places. It is not only the interior factor that matters, but it is important to note that the place has at least a couple of open exits, separation between tables and a medium-low occupancy.

“My impression is that closed places with little ventilation, where you enter and can smell the room … you already know that the air there is not changing much, but the important thing is not so much to trust the impressions but to measure it with these devices”

concludes the professor from the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Its use begins to spread

Recently, the Community of Madrid has suggested to the hospitality industry to get these type of sensors, but the truth is that many institutions have already advanced.

Miguel Palacios, a professor at ESCP Business School, heard first-hand from his cousin José Luis Jiménez the wonders of CO2 meters as sentinels of contagion risk and proposed applying it at school, where he teaches Family Business Innovation and Management. In addition to the usual recommendations for capacity or temperature measurement, the campus, located in the Puerta de Hierro area, now has about twenty meters monitoring the classrooms.

Each of them reports the CO2 concentration in the classroom, which allows the janitor, who has all the meters controlled on a tablet, to discover when someone has closed the classroom window, something that is immediately obvious because the CO2 measurements in one of them start to scale. At a glance, they can see how the entire building is ventilated.

“Every ten minutes we receive updated data,” he explains.

In addition to this they have incorporated air purifiers in each classroom. The result is that since the beginning of the course they have not registered any contagion in their facilities. Of course, these measures do not completely eliminate the risk of contagion, but they do eliminate the risk of super contagion.

The only price to pay is a little cooler room temperature.

“We tell the students that they have to come warm and not take off their coat,”

says Palacios.

Methodology

The meters used in this report are from the Latvian brand Aranet and the Aranet4 HOME model, one of the few on the market that has NDIR or infrared measurement technology. For Jiménez, they are one of the most comparable to the meters he uses in the laboratory. Although the latter has a higher price (between 199 and 299 euros depending on the model) than other meters, the demand is sometimes so great that it is quite difficult to find one.

In reality, although less precise or with a greater margin of error, non-NDIR devices capable of measuring CO2 can be found from 30 euros and the vast majority are below 100.

“It does not have to be the best possible, but it does not have to be bad” says Jiménez. “There are some that are based on electronic noses and the CO2 will still increase when you put on hydroalcoholic gel or there is humidity.”

“The most important thing is that the meter that we are going to buy has a built-in NDIR sensor since this will give us greater precision in measuring CO2,” says Cristian Navarro, Aranet’s manager in Spain. “Normally our clients have been researchers or companies that want to improve the quality of the air in their surroundings, but now the demand is much higher: from individuals to universities, restaurants, companies with offices, schools …”

To carry out all these measurements we have established several rules:

- Do not place the meter where people can breathe directly at it since breathing could affect the measurements

- Do not place it in doors or currents so that the measurement is as representative as possible of the air that is being breathing in an environment

- Leave it in one place for at least a quarter of an hour (the meter used takes measurements every 1-5 minutes) to make it representative.

The text above is translated, the original article available at this link.